Holding up the Mirror

Transcribed talks by Ratnaghosa

Talk six of six on patience or kshanti

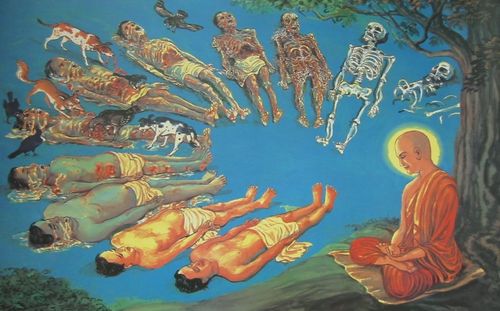

I began the first talk in this series of talks on Kshanti with a quote from the novel Kim, by Rudyard Kipling. The quote was a description of the Tibetan Wheel of Life. The Tibetan Wheel of Life is as you know a visual depiction of the cycle of mundane existence. As the centre of the wheel of life are a cock a snake and a pig biting each others tails. They represent greed, hatred and spiritual ignorance, the basic mental poisons which keep the whole cyclic process going. T

he second circle of the wheel shows people descending and ascending, which indicates that within the round of mundane existence it is possible to go downwards into more negative mental states or upwards into more positive mental states. The third circle of the Wheel shows six realms of conditioned existence into which we can be reborn. They are the god realm, the realm of the titans, the hungry ghost realm, the hell realm, the animal realm and the human realm. These can also be seen to represent mental states that we inhabit from day to day or even from minute to minute.

The outermost circle of the Wheel is a pictorial representation of the twelve links in the realm of cyclic conditionality which describe how the whole process of mundane existence goes round and round, lifetime after lifetime. In that first talk I said that Kshanti was the antidote to the snakebite of anger and hatred. In the second talk on Patience I said that patience created a gap between feeling and the response to feeling.

This corresponds to the point on the outer circle of the Wheel of Life between feeling and craving. This is the point where it is possible to break free of the reactive round of cyclic conditionality and move on to the creative spiral of accumulative conditionality. In the third talk I said that forgiveness was the creative response that broke the cycle of negativity, forgiveness being a letting go of any desire for revenge or retaliation.

Tolerance is a maintaining of the positive emotion and clarity of mind that assures progress on the spiral path and Receptivity to the sublime Truth of the Dharma is what eventually allows us to have knowledge and vision of things as they really are. This point of Insight is the point of no return. From this point we are assured of gaining Enlightenment.

The state of Enlightenment is described in various ways. It is described as Nirvana, Knowledge of the destruction of the mental poisons, an unconditioned way of seeing the conditioned, realisation of the One Mind and so on. None of the concepts is adequate. Language is necessarily dualistic and therefore incapable of encompassing experience beyond the dualism of subject and object.

The experience of Enlightenment can be hinted at in poetry and metaphor, but not really described. Another approach to communicating the experience of Enlightenment is through the language of images and symbols. One of the most important sets of images and symbols is what is known as the Mandala of the Five Jinas or Five Buddhas. The mandala is a symbol that occurs all over the world and it indicates a state of wholeness or completeness. The Mandala of the Five Jinas indicates the richness and abundance of the Enlightened Mind by depicting five Buddhas, each of which represents Enlightenment in its totality and each of which emphasises a particular aspect of Enlightenment.

Traditionally, you enter the Mandala in the East, which, strangely enough is at the bottom of the picture. The Buddha in the East is Akshobya, the Imperturbable. Then you move around to the South on the left hand side of the picture and here you find Ratnasambhava, the Buddha of Beauty and Generosity. In the West, at the top of the picture, you met Amitabha, The Buddha of Love and Compassion. The Buddha of the North is Amoghasiddhi, the Buddha of Action and Fearlessness. At the Centre of the Mandala is Vairocana, the Illuminator.

Each of the Five Buddhas is associated with a particular colour, hand gesture, animal and emblem. All of this amounts to an extraordinarily rich symbolism. Each of the Buddhas is also associated with a particular mental poison. The five poisons are greed, hatred, spiritual ignorance, pride and envy. It is as if the Buddhas represent the complete transformation of a particular poison into something totally positive.

The poison of hatred, anger or ill-will is associated with Akshobya. Kshanti is the method by which hatred and anger is to be transformed and Akshobya is the end result of the complete transformation of hatred. This is the main connection between Ksanti-Paramita and the Buddha Akshobya. In the course of this talk I will draw out some more connections between the symbolism and attributes of Akshobya and the different aspects of Kshanti.

The Sanskrit word ‘akshobya’ means unshakeable. The Buddha Akshobya received the name because he took a vow in a previous lifetime never to give way to anger or malice, never to be unethical and many other things. Over lifetimes he was unshakeable in holding to his vow and thus became eventually the Buddha Akshobya, the unshakeable or imperturbable. Unshakeable means unwavering or firm and imperturbable means calm.

This aspect of Akshobya the represents the dedication which is unwavering and calm, not easily disrupted. It is the patient, persistent and consistent effort we met earlier in relation to the topic of patience. What the unshakeability and imperturbability of Akshobya is teaching us is that we must be determined and steadfast in our practice of the Dharma and not allow ourselves to be put off or dispirited by minor setbacks or upsets.

All too often we are lacking in stamina. We don’t perhaps have sufficient motivation or vision to rouse us to heroic effort. Politicians for instance seem to have tremendous stamina although they may not put it to very skilful use. People in theatre or pop stars have stamina.

In the world of business people exert themselves strenuously. It seems that when people are motivated enough they can perform great feats of energetic striving. Often the motivation is quite selfish in character. In the spiritual life we need that kind of stamina too. Wee need it in order to make the consistent effort that personal development demands and we need it if we are to be of help to others. Sangharakshita commented on this in a study seminar he [held / lead] in 1980.

He said, “We are so effete in the spiritual life, more often than not. We cant stand any sort of strain; after any bit of extra effort we have to go away and rest, have a little holiday, sit down for a while, play a record and take things easy. Its pathetic! (Laughter.) Here you are, aspiring to gain Enlightenment, which is after all the most difficult thing you can possibly propose to yourself, and look how easily one usually takes it – what an easy time one gives oneself. And there, [[on the other hand]] are people aiming at the very inferior, trivial, easily attained things like the Presidency of the United States.

Just look at the massive effort they are putting in – it puts us to shame! Perhaps you think he is exaggerating for effect. I don’t think so. I think he is probably even sugaring the pill. If you read the life of Sangharakshita or of other great Buddhists ore remarkable practitioners from other religious traditions, you will find they all had great stamina and the ability and willingness to make consistent effort in pursuit of their goals.

How can we develop stamina? The answer is with practice. We touched on this earlier in the talk on patience when Shantideva was quoted as saying, “There is nothing which remains difficult if it is practised. So, through practice with minor discomforts, even major discomfort becomes bearable” [ KS Verse 14] If we are to develop stamina we need to learn how to endure discomfort, whether it is physical discomfort or emotional discomfort.

Endurance is an aspect of Kshanti that I haven’t said much about. In the Dhammapada there are some verses that use the image of an elephant in connection with endurance. Verse 320 says: “I will endure words that hurt in silent peace as the strong elephant endures in battle arrows sent by the bow, for many people lack self-control.” And verse 327 says: “Find joy in watchfulness: guard well your mind. Uplift yourself from your lower self, even as an elephant draws himself out of a muddy swamp.” Verse 325 warns us against too much comfort-seeking and distraction. “The man who is lazy and a glutton, who eats large meals and rolls in his sleep, who is like a pig which is fed in the sty, this fool is reborn to a life of death.” The elephants who bear the throne of Akshobya on their back can serve to remind us of the need for endurance.

The elephants, because they are beneath the lotus, which symbolises the Transcendental, are here to represent the highest reaches of the mundane. They symbolise the unshakeable, imperturbable qualities that were perfected by Akshobya before he gained Enlightenment. They are the steadfast, calm, fearless foundation for the ego-shattering experience of Insight. They represent the ability to endure the ultimate discomfort of having no place to hide from the fierce light of Reality. The quality of endurance is probably not very popular these days.

Comfort and instant gratification are the hallmarks of our society. Endurance and the ability to postpone gratification of desires are hallmarks of the spiritual life. In his latest book “The Sibling Society”, Robert Bly argues that people no longer want to grow up and face the difficulties of adulthood. Instead we are creating what he calls a sibling society, a society of adolescents which demands little in the way of responsibility and difficult work. He says; “When enough people have slid backward into a sibling state of mind, society can no longer demand difficult and subtle work from its people – because the standards are no longer visible. Without the labour of artists, for example, to incorporate past achievements – in brushwork, in treatment of light, in depth of emotion, in mythological intensity – people with some talent can pretend to be genuine artists.

Their choices seem to be to cannibalise ancient art, or to create absurdly ugly art that “makes a statement”. They don’t ask themselves or each other for depth or intensity, and most contemporary critics pretend not to miss them. Bly goes on to define an adult as “a person not governed by the demands for immediate pleasure, comfort and excitement.” And in confessional tone he says “The adult quality that has been hardest for me, as a greedy person, to understand is renunciation. The older I get, the more beautiful the word renunciation seems to me.” If Bly is right and I suspect he has a point, then we have the task of not only counteracting our own tendencies to shy away from the uncomfortable, but also the task of going against a strong trend in the society around us.

We need to be on out mettle. Nothing worthwhile is achieved without dedicated effort and willingness to endure whatever privations occur along the way. If we want to achieve anything worthwhile with our lives we need to learn to endure and thereby build stamina. Sangharakshita touches on this when he says: “Perhaps our daily routine should be such that we are strengthened rather than weakened.

Not too many mornings lying in bed; not taking things too easily; not too many holidays; not too many visits to the cinema. Quite apart from the question of distraction, all this can be very weakening. Under modern conditions we can end up rather weak creatures if were not careful. We very rarely have to work hard day after day, week after week, month after month, as many people in the world still have to do just to survive. We very rarely work for the Dharma with that sort of vigour and indifference to hardship and discomfort.” So this is the Elephant – the elephant of endurance is not disturbed or perturbed or put off by a few criticisms or by people being difficult. Endurance depends on a higher vision which sustains us through the discomforts of spiritual development. In the palm of his left hand Akshobya holds a vajra. The vajra symbolises a union of opposites.

One end of the vajra represents the mental poisons and the other end the five Wisdoms. The vajra is also a symbol of great energy directed toward breaking through to Enlightenment. The negative quality associated with Akshobya is anger or hatred. So the vajra here is a representation of the transformation of hatred into wisdom and of the enormous energy that is released by that transformation. As Vessantara puts it in “Meeting the Buddhas” : [] hatred can be redirected and used to further our development. When we are experiencing it there is often a kind of clear, cold precision to the way in which we see the faults of things.

It is a state completely devoid of sentimentality or vagueness. We just have to see what the real enemy is. Once we hate suffering in ignorance, and are hell-bent on destroying them, that energy leads us to Akshobyas Pure Land rather than into the hells of violence and despair. We transform our anger through the practices of patience and forgiveness, thus releasing energy for further spiritual development. Our anger and hatred is often born out of our fear and insecurity.

It is a defence against all that threatens our egotism. By letting go of anger we allow ourselves to feel the fear and also paradoxically gain confidence in ourselves as spiritual beings. We can re-direct the energy of our anger into taking those small risks that enable us to go beyond our current limitations. In this way we can become more confident and secure in our individuality and less prone to taking offence or holding on to grudges. The vajra is a profoundly optimistic symbol, indicating not only that all negative emotions can be transformed in Transcendent Wisdom, but that the seeds of Wisdom lie in those very negative emotions. A similar idea is expressed by the fact that the lotus, symbolising transcendental attainment has its roots in the mud of mundane concerns.

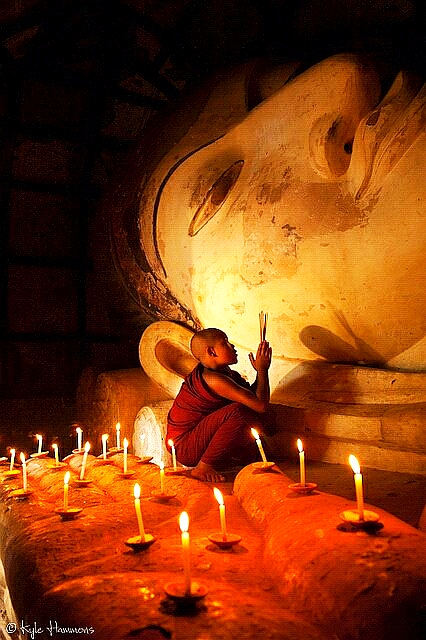

The right hand of Akshobya touches the earth. We encountered the earth- touching mudra (bhumisparsa-mudra) in the previous talk on receptivity. There we saw that at the time of the Buddhas Enlightenment he was challenged by Mara to produce a witness to testify to his right to sit on the Vajrasana, the spot where all the Buddhas of the past had gained Enlightenment.

In response, the Buddha touched the earth and the Earth Goddess arose and testified that he had practised the Perfections in hundreds of previous lives and was therefore entitled to sit on the Vajrasana. In more conceptual terms we are told elsewhere that at the time of his Enlightenment the Buddha was able to remember all his previous lives. So this episode refers to an overcoming of all vestiges of doubt by referring back to the experience of practising virtuous conduct over many lifetimes. This is also a reference to the law of Karma which states that skilful activity has beneficial consequences for us.

If we behave skilfully we can expect to experience the fruits of that activity at some time. At the time of his Enlightenment the Buddha was experiencing the fruition of his skilfulness over many lifetimes. We can be confident that if we want to achieve spiritual progress and happiness, the law of Karma guarantees our success so long as we make the effort. If we get into a mood of doubting or despondency, we can look back at whatever is positive in our lives and feel assured that it is not lost or wasted. We can use that as a new starting point to stabilise us.

To touch the earth of our skilful actions is to gain confidence and stability. Perhaps sometimes we should literally touch the earth in a ritual manner to feel for ourselves the stabilising effect of the bhumisparsa-mudra and all that it symbolises. Try it sometime when you’re sitting in meditation posture. In terms of Kshanti, we saw earlier that this is an aspect of receptivity. We could say it is receptivity to the immutable law of Karma. The next aspect of Akshobya Id like to look at is the most important quality of all – the Mirror-like Wisdom.

It is the Wisdom of a Buddha which is the essential quality and when we contemplate or meditate on an archetypal Buddha we are trying to open up to that Wisdom and allow it to permeate our whole being to the point where we become the Wisdom/ When we contemplate Akshobya we are trying to make ourselves receptive to his essence, which is the Mirror-like wisdom. The Mirror-like Wisdom reflects absolutely faithfully everything that comes into contact with it. It sees everything just as it is, with no preferences, no judgments, no ideas added on.

The mind which is suffused with the Mirror-like Wisdom is completely impartial. It feels no need to choose one thing above another, it is not affected by one thing more than another, just as a mirror reflects faithfully what ever is put in front of it and doesn’t retain some reflections and reject others. The mind which has attained to the Mirror-like Wisdom has of course transcended all duality of subject and object. It has seen through the illusory nature of conditioned existence and is beyond all distinctions, event the distinction between Samsara and Nirvana.

Has this any relevance for us on our comparatively low level of spiritual insight? Is there any lesson we can take from the Wisdom of Akshobya and apply it to our lives right now? And how does this relate to Kshanti? There are two connections I would like to make which I think are relevant to us here and now. These are to do with the areas of clear thinking and objectivity. The Mirror-like Wisdom, in particular, puts me in mind of clarity of thought. It seems to emphasise the absence of vagueness or confusion. In one of the sets of fifteen points for Order Members which Sangharakshita outlined some time ago, there is an exhortation to think clearly. He even suggested that Order Members should study logic, to help them to think more clearly.

The opposite of clear thinking is of course vague or woolly thinking, which isn’t really thinking at all. Usually we just let our minds wander around, like slightly demented characters, picking up pits and pieces here and there. Then we construct all sorts of views and opinions out of these bits and pieces and imagine that we’ve had some ideas. Most of our ideas are not our own, but simply an amalgam of various things we’ve heard or read, put together by our conditioned prejudices, to create a world view that keeps us reasonably sane. One of the first things we need to do if we are to develop clear thinking is to become aware of the extent to which all out thinking is influenced by the conditions which have surrounded us since birth.

Although we may like to think of ourselves as independently minded and wise to the world, we are more likely to be completely immersed in views and ideas that we simply ingested from the world around us in the same way that we learnt to speak. In fact the analogy with learning to speak is not just an analogy, because the very language carries meaning and ideas in it which we accept unquestioningly until something erupts in our experience that makes us sit up and take notice. In Buddhist terms it is not sufficient however for us to analyse of deconstruct language.

What we really need to do is develop greater mindfulness and try to filter all our thinking through the purifying insights of Right View. To do that we need to have Right View or at least know what Right View is. There can be no real or fruitful communication in the Sangha if we are starting from different or even opposing world views.

For instance, to give an absurd example, if your basic world view is that suffering will be brought to an end by the demise of Capitalism and the dictatorship of the proletariat and my basic world view is that the extinction of suffering depends on the individual making the effort to develop spiritually in co-operation with other like-minded individuals, then although we may seem to speaking the same language and even in broad agreement at times, in fact we will be worlds apart and not communicating at all. In the Sangha we want to foster genuine communication and therefore we need to establish the basis of Right View and carry on our discussions in terms of Right View. To do this we have to make an attempt to weed out the wrong views that inevitably could our minds, because the world we live in is awash with them. Just before Sangharakshita encouraged clear thinking he exhorted Order Members to reduce input.

There is a direct connection between reducing input and clear thinking. What we feed into our minds is what comes out as views and opinions If we feed our minds on a daily dose of newspapers and television, that is what will have the biggest influence on our thinking. If we feast our minds on a daily repast of Buddhist scriptures and commentaries then they will begin to form the basis for our thinking and as Buddhists that would be an altogether healthier diet for us. It is not just the content of what we read that affects out thinking but also the style.

If we read books that are written by people who can think clearly and express themselves clearly, that will help us to think clearly ourselves. I think Sangharakshita is a supreme example of someone who thinks and expresses himself and therefore reading his books can be of great help in training ourselves to think clearly. The topic of clear thinking is not unrelated to the topic of objectivity. To be objective we need to be able to distinguish opinions from facts.

This is not necessarily very common. A simple example that is given is the way people say something like its a terrible day when what they mean is its raining. The terrible day is a value judgment and a matter of opinion. The rain is a fact. So in order to be objective and therefore truthful we need to be able to tell what is a value judgment or opinion and what is a fact. So for instance when we use terms like always and ever as in “I’m always last to know what’s going on” or “Nobody ever listens to me” we are probably being poetic rather than factual.

But its important for us to realise that, otherwise we start to believe ourselves on an emotional level and that can have significant consequences. I’m not suggesting that we should never use idiomatic speech, but rather that we should try to be clear about what is subjective and what is objective in our communication. Often we hold very strongly to our views and this is for very subjective, emotional reasons and one way of beginning to loosen our attachment to views is to start to see the element of subjectivity and emotionality and try to distinguish that from what is objective and factual.

The basic wrong view that we all suffer under is the view that we are a separate self or ego-identity and this conditions most of out other views. This sense of separate selfhood, as I said in the first talk in this series, is the fundamental prejudice from which all others flow. To begin to undermine or attenuate this view we need to approach it from many angles. We need to cultivate self-metta, we need to practise generosity, we need to immerse ourselves in

Buddhist study, we need to experience solitude and we need to make an effort to distinguish what is objective from what is subjective in our thoughts and words.If we achieve greater clarity we will be able to practise greater tolerance towards those who are different from us and those we disagree with, without being vague or woolly or compromising our real beliefs. The Mirror-like Wisdom of Akshobya is neither subjective nor objective.

It is Transcendental and therefore beyond views altogether. Here Reality is experience, experience is Reality. As Vessantara puts it in Meeting the Buddhas – when we enter the mandala “we see the deep blue figure of the Immutable Buddha, holding the thunderbolt sceptre of Reality which smashes through all our ideas and concepts about it.

At the same time the dark blue fingertips of his right hand touch the earth, the earth of direct experience, which is the only thing upon which any of us can finally rely.” Now we are coming to the end of this series of talks on Kshanti and to the end of this talk on Akshobya. I hope that you have found something to interest you, perhaps challenge you or even inspire you, in some of what has been said.

he subject of Kshanti hasn’t been exhausted by any means. For instance I have deliberately not mentioned anutpattika-dharma Kshanti, because that is the highest practice of Kshanti. It is the patient acceptance of the non-arising of dharmas, or in other words the patient acceptance that all phenomena are ultimately not real even though they are perceived and therefore exist to the extent that they are perceived.

So to finish off this series of talks on Kshanti I will just leave on the mountain peak of the Diamond Sutra with its description of this highest level of Ksanti-Paramita. This is what it says, “Moreover, Subhuti, the Tathagatas perfection of patience is really no perfection. And why? Because, Subhuti, when the king of Kalinga cut my flesh from every limb, at that time I had no perception of a self, of a being, of a soul, or a person/ And why?

If, Subhuti, at that time I had a perception of a self, I would also have had a perception of ill-will at that time. And so, if I had had a perception of a being, of a soul, or of a person. With my superknowledge I recall that in the past I have for five hundred births led the life of a sage devoted to patience. Then also have I had no perception of a self, a being, a soul, or a person.”

Source: http://ratnaghosa.fwbo.net