Transcribed talks by Ratnaghosa

Talk one of six on patience or kshanti

In the novel “Kim” by Rudyard Kipling, one of the main characters is a Tibetan Lama. Kim becomes his disciple or chela and the Lama, who is an artist, paints a picture of the Wheel of Life so that he can use it to teach the Dharma to Kim.

“When the shadows shortened and the lama leaned more heavily upon Kim, there was always the Wheel of Life to draw forth, to hold flat under wiped stones, and with a long straw to expound cycle by cycle. Here sat the Gods on high – and they were dreams of dreams. Here was our Heaven and the world of the demi-Gods – horsemen fighting among the hills. Here were the agonies done upon the beasts, souls ascending or descending the ladder and therefore not to be interfered with. Here were the Hells, hot and cold, and the abodes of tormented ghosts. Let the chela study the troubles that come forth from overeating – bloated stomach and burning bowels. Obediently then, with bowed head and brown finger alert to follow the pointer, did the chela study.”(1)

The Tibetan Wheel of Life is a very comprehensive symbol of the world, a symbol of our minds and our lives, both individually and collectively. In the centre are a cock, a pig and a snake, biting each other’s tails. They represent the mental poisons of greed, hatred and spiritual ignorance which are the forces that keep us going round and round in circles of suffering and unsatisfactoriness. The pig represents spiritual ignorance, the unwillingness to recognise that actions have consequences, that it is possible to dwell in higher states of consciousness and that all things are impermanent. The cock represents greed or craving. According to Sangharakshita this is a state “in which the self or ego reaches out towards the non-self or non-ego with a view to appropriating and even incorporating it, thus filling the yawning pit of its own inner poverty and emptiness.”(2) The snake represents hatred, ill will and anger. Hatred is the desire to destroy whatever prevents us from possessing the things or people we crave. The snake of ill-will lashes out with its venom at whatever gets in the way of its greedy desires.

We are concerned with this snake when we look at the topic of Kshanti. Kshanti is the antidote to snakebite, the antidote to hatred, ill will, resentment, jealousy, anger and a lot of other poisonous mental states. Hatred or ill will is with us all the time, from the mild irritation and annoyance we experience at not getting our own way, to self-hatred, outbursts of anger, jealousy, competitiveness, narrow-minded rationalism, racism, ideological politics and so on. Ill will manifests itself in all sorts of ways and a glance at any newspaper will confirm how ubiquitous it is (not that newspapers give a particularly balanced account of the world we live in). There is murder, rape, child abuse, warfare, ethnic cleansing and bigotry of all sorts. Then there are the jealousies of lovers and former lovers, the breakdown of relationships between parents and children, the anger of motorists and pedestrians, the harsh words of political rivals, and so on. Lack of self-esteem or ill will towards ourselves is also very widespread.

Anger

Sangharakshita makes a distinction between two different kinds of anger. (3) There is the anger of frustration which wants to remove all obstacles to communication, wants to remove whatever is blocking communication. This can be very good. It is energy that wants to move beyond limitation. The there is the anger of rage or hatred which wants to remove the person. This is anger out of control, sinking below the human level. The point is that anger is not necessarily a bad thing, but usually we do not maintain enough awareness to be able to direct it positively. The anger of frustration can easily tip over into the anger of rage and hatred. There is not just anger which is demonstrative but also anger which is quiet. Quiet anger is characterised by incessant obsessive thoughts which may manifest as stubbornness or an ‘atmosphere’ of ill will. Sometimes people on the spiritual path think that they should not be angry and try to bury or dismiss any anger that arises. However, metta is not something that can be forced. It is necessary to experience anger in order to transform it. To experience it does not mean to express it. We do not need to splash others with the muddy waters of our anger. It is not a case of express it or repress it. It is a matter of experiencing and transforming.

Energy

There are multitude of forms in which hatred or ill will manifests within us and all around us. What are we going to do about it? How can we withstand the onslaught of poisoned darts? Well, the first thing to note is that we need energy to deal with it. In Buddhist terms we need Virya, the energy which transforms negative emotion and unskilful actions into positivity and skilfulness. So Kshanti, the antidote to the snakebite of hatred and ill will, is not something passive or anaemic. It is an energetic quality. It requires strength and robustness. There is no Kshanti without Virya. Kshanti is a term with many meanings. According to the Pali-English Dictionary, khanti (which is the Pali for the Sanskrit Kshanti) means patience, forbearance and forgiveness. However in his book “The Drama of Cosmic Enlightenment” Sangharakshita enlarges on this; “It is difficult to translate Kshanti by any one English word because it means a number of things. It means patience: patience with people, patience when things don’t go your way. It means tolerance: allowing other people to have their own thoughts, their own ideas, their own beliefs, even their own prejudices. It means love and kindliness. And it also means openness, willingness to take things in, and, especially, receptivity to higher spiritual truths.”(4) So in this talk I am going to look at Kshanti in terms of patience, forgiveness, tolerance and receptivity and relate Kshanti to enlightenment as represented by the Buddha Akshobya. And in the following talks I will go into each of these areas in more detail.

Six Perfections

But before I go into Kshanti in more detail, I would like to say something about the Six Perfections and the Bodhisattva Ideal to put the topic in context. The term bodhisattva means ‘Enlightenment being’. A bodhisattva is someone in whom the Bodhicitta has arisen. The word ‘citta’ means heart and mind. Bodhicitta is ‘Enlightenment heart and mind’. The arising of the Bodhicitta is the arising of intensely strong desire or urge to gain enlightenment for the sake of all beings including oneself. When one has this experience if intensely strong desire to gain enlightenment for the sake of all, one can no longer fall back from the spiritual life, one is now on the path irreversibly, but effort is still required. Traditionally, there are two aspects to the Bodhicitta, the vow aspect and the establishment aspect. The vow aspect is the Bodhisattva experience of the arising of the Bodhicitta in terms of a vow to do whatever is necessary to help all beings attain Enlightenment.

One of the most famous traditional sets of vows is called the Four Great Vows and they are (1) May I deliver all beings from difficulties. (2) May I eradicate all defilements. (3) May I master all dharmas. (4) May I lead all beings to Buddhahood There are other traditional sets of vows and it is also traditional for any particular bodhisattva to create his or her own set of vows. So these vows are the expression of the urge to enlightenment for the sake of all beings. Then the bodhisattva has to put them into practice.

Putting them into practice is what the establishment aspect of the Bodhicitta is about. The establishment aspect of the Bodhicitta is expressed in the practice of the Six Perfections. These could perhaps be more correctly called ‘Perfectings’ since they do not represent something static. They represent the practice of constant transcendence. The Six Perfections are Dana (giving), Sila (ethics), Kshanti, Virya (energy), Dhyana (meditation) and Prajna (Wisdom). These Six Perfections are an “amplified restatement” of the Threefold Way of Sila, Samadhi and Prajna, which was the way of the monk in the Hinayana tradition. This Threefold Way was later extended to become the fourfold way of Dana, Sila, Samadhi and Prajna – the way of the lay person and then in the Mahayana tradition this was further extended to become the Six Perfections with the addition of Kshanti and Virya. Kshanti and Virya are therefore distinctly bodhisattva-like virtues. They are the heroic virtues that need to be cultivated in order to undertake the vast cosmic task of gaining Enlightenment for the sake of all beings. The energy to be persistent and consistent for lifetimes and the patience to work, live and communicate with others who might sometimes appear to be going in the opposite direction. Strictly speaking, the Six Perfections are only Perfections when Insight has arisen. Therefore Prajnaparamita, the Perfection of Wisdom is most important, because it is what makes all the others Perfections. However, the Six Perfections can and indeed must be practised on a mundane level too, to prepare the ground for the arising of the Bodhicitta.

The Bodhisattva Ideal is the altruistic ideal taken to perfection and it is the ideal which is at the heart of the WBO and FWBO. To train ourselves to be more altruistic we need to attempt to practise the Six Perfections. And it is worth stating that the Six Perfections can be seen as a progressive path from Generosity to Wisdom. I would like to take this opportunity then to once again emphasise the great importance of developing a spirit of generosity in all our interactions. The spirit of generosity and activity of generosity forms a sound basis for all spiritual practice. Without it we will go round in self-obsessed circles. So although we have already had our Year of Dana and our Year of Ethics, it is necessary that we remember that the third Paramita, Kshanti, is to be practised in the context of the practices of generosity and ethics.

Patience

So first of all, Kshanti as patience. In the Survey of Buddhism, Sangharakshita suggests that the spirit of the Perfection of Patience is well illustrated in the Parable of the Saw: “Brethren, there are these five ways of speech which other men may use to you:- speech seasonable or unseasonable: speech true or false: speech gentle or bitter: speech conducive to profit or loss: speech kindly or resentful When men speak evil of ye, thus must ye train yourselves: “Our heart shall be unwavering, no evil word will we send forth, but compassionate of others welfare will we abide, of kindly heart without resentment: and that man who thus speaks will we suffuse with thoughts accompanied by love, and so abide: and, making that our standpoint, we will suffuse the whole world with loving thoughts, far-reaching, wide-spreading, boundless, free from hate, free from, ill-will, and so abide.: Thus, brethren, must ye train yourselves. Moreover, brethren, though robbers, who are highwaymen, should with a two-handed saw carve you in pieces limb by limb, yet if the mind of any one of you should be offended thereat, such an one is no follower of my gospel.”(5) Here we see the spirit of metta at work. The spirit of patience is metta. It is an attitude of gentleness and love, that is strong enough, robust enough, to smile and forgive in the face of all provocation and hurtfulness.

We need to develop an attitude of patience towards both ourselves and others. Patience is the gap between our experience of being hurt and our response to being hurt. Without the gap there is simply a knee-jerk negative reaction. With the gap created by the exercise of patience there is a possibility of a more creative and positive response. We need to exercise patience in relation to others because we are all intimately connected by the threads of our common human consciousness. It we don’t exercise patience, we keep the fires of hatred and ill will burning by adding the fuel of our negative reactions to the sparks of other peoples anger and irritation. If we do practise patience we create the possibility for change to take place. Instead of sending the Wheel of Life into another spin, we slow it down. As the Dhammapada says, “Hate is not conquered by hate: hate is conquered by love. This is a law eternal”(6). This love is Kshanti in the form of patience.

We also need to practise patience towards ourselves. We need to be patient with our progress in the spiritual life. We cannot force-grow ourselves. We have to set up conducive conditions and make a consistent effort. Then we will grow. But we all grow and change at a different pace and in different ways. We need to be aware that spiritual progress is a process, a process of change that takes place on different levels of our being. Sometimes it may not be apparent to us that we are growing and changing, but if we are making a consistent effort and are sincere in out aspiration to develop metta and mindfulness then we can be assured that we are making progress and it will become manifested in time. To be impatient with ourselves only hinders out growth because it is a form of self-hatred. We should also be patient with the spiritual growth of others. Sometimes people may say, “You’re a Buddhist. You shouldn’t be angry.”, or greedy or whatever. This misses the point about what it means to be a Buddhist. A Buddhist is someone who is making an effort to grow and develop spiritually, making an effort to be more skilful, making an effort to be more kind and more aware. A Buddhist is not someone who is perfect. That is a Buddha. We need to be patient with others and expect them to be imperfect and forgive them for it.

Forgiveness

This brings me on to Kshanti as forgiveness. Forgiveness is the creative response that emerges from the gap created by patience. When we feel hurt or upset by someone, if we manage to be patient, we create time for reflection. When we reflect we may come to realise the uselessness and stupidity of retaliation, which only creates further hurt and upset. We may even on reflection be able to see we have been presented with an opportunity to go beyond ourselves, to go beyond self even. In our world of separate selfhood, the logical thing is to defend and attack. In the world of interconnected humanity, the real world, the intelligent way to respond to hurt and upset is with patience and forgiveness. Forgiveness takes us beyond our limited self-interest and self- indulgence to what is best in the interests of both self and other. It is in the common interest of all of us to stop the endless downward spiral into anger, hatred and violence. So it is in the common interest to let go of grudges and resentments and wholeheartedly forgive.

Tolerance

As well as patience and forgiveness, Kshanti also means tolerance. It might be good to say what tolerance is not. Tolerance is not weakness. Tolerance is not agreement. Tolerance is not supercilious condescension, as someone once defined it to me. Tolerance is the willingness to allow others to have their own beliefs, their own ideas, their own thoughts and feelings. Intolerance is an unwillingness to allow others to have different beliefs, views, ideas and so on and intolerance often leads to violence, oppression and persecution. It is possible to strongly disagree with someone, to totally disagree with them, but still allow them to have their own beliefs and views. Tolerance promotes communication, not persecution. In communication there can be disagreement and a vigorous exchange of views, but this doesn’t have to lead to persecution, or even to ill will. According to the Buddha, if we feel ill will towards those who disagree with us, we are not practising the Dharma. Tolerance is a response of metta to that which is different from us and also a response of metta to that which is repugnant of disagreeable to us.

We can also be tolerant towards ourselves. Most of us find ourselves in internal conflict from time to time. It’s as if there are different aspects of our psyche vying for dominance and sometimes an internal dialogue goes on which can be quite violent. The more we develop an attitude of tolerance, the more we can introduce tolerance into our own internal dialogues and accept that the conflict cant be won, but only transcended. Tolerance is all too often lacking in the world about us It is as if people don’t know how to disagree or be different without anger or è ill will. This is again due to the deluded sense of separateness that we all suffer under. This sense of separate selfhood is the fundamental prejudice and the feelings of being threatened and the need for defensiveness and oppression that follows in its wake cause untold misery in this world. The more we can undermine this prejudice of separateness, the more we will be able to tolerate difference and disagreement. The more tolerant we become, the more peaceful will be our immediate world and eventually the wider world. In order to undermine our delusion of separate selfhood, we need to hear the Dharma and to reflect on the Dharma and allow it to change us. In other words, we need to be receptive to the Dharma.

Receptivity

Receptivity is another important aspect of Kshanti. Receptivity does not mean passivity. To be receptive to the Dharma means to allow yourself to be affected by the Dharma. To be affected by the Dharma, you have to hear it, reflect on it and put it into action. You have to listen creatively and make connections between what you are hearing and the day to day details of your life. It is not possible to be receptive to the Dharma unless you have some feeling for the reality of spiritual hierarchy. The Dharma as Insight and experience is mediated through concepts and images and those concepts and images come to life and are distilled into living precepts by those who have made the effort and have grown and developed spiritually. When you recognise that others are more spiritually developed than you are you can begin to learn from them. You enter into a relationship of spiritual friendship with them and through that you begin to imbibe the spirit of the Dharma as well as the letter. The spirit of the Dharma is what is most important for transforming our lives. It is the spirit of the Dharma that we need to be receptive to. We need to allow the spirit of the Dharma to change us.

Kshanti, in the form of receptivity, is an antidote to our attachment to views. We all have so many views; views about ourselves, views about others, views about the world, views about history, views about politics, views about religion, views about Buddhism even. And we are often very attached to our views, we identify with our views, indeed to some extent we are our views. The Dharma challenges our views. It challenges our views fundamentally. Most of our views and most of the views that have currency in the world are the product of unenlightened consciousness and are therefore, to say the least, limited and often simply wrong. For instance, just to take a very simple and widespread view that we are all affected by – the view that money provides security. From the point of view of the Dharma, from the standpoint of enlightened consciousness, this is a wrong view and, as such, a hindrance to spiritual progress. It is in this way that our receptivity to the Dharma can turn us upside down and totally transform us.

If we are receptive to the Dharma we will be confident in our ability to change, because nobody is beyond redemption. The law of conditionality, that everything arises in dependence on conditions, means that if we make an effort we will progress. And this is indeed what experience shows. The Dharma is concerned with individual emancipation from the fetters of limited awareness. Receptivity to the Dharma also involves receptivity to ourselves. We need to allow ourselves to experience our thoughts and feelings and gain self-knowledge through reflection. We need to know who we are in order to change and grow. What we may find, as we look more closely through the practices of meditation and reflection, is that we are not one, not a unified individual, but that there are several strands or tendencies to our being. Sometimes, even often, these tendencies are in conflict. So we need to become aware of this, listen to the conflict, experience it and in this way transcend it.

Receptivity to ourselves and to the Dharma could be seen as an act of imagination. We do not have to allow ourselves to be limited by what is, we can imagine what could be. We don’t deny what is actually happening or what we are actually experiencing, but we see it all in a much wider context. We listen to the vast and universal perspective of the Dharma and allow it to become a motivating force in our lives. The vast and universal perspective of the Dharma is encountered in the concepts of Wisdom and Compassion, the Bodhisattva Ideal, the law of Conditionality, the Six Perfections and so on. It is also encountered in the images and mantras of the archetypal Buddhas and Bodhisattvas Those figures represent Enlightenment in all its beauty and profundity and in all its myriad qualities.

Akshobya

One of the most common and important images in the whole of Buddhism is the mandala of the Five Jinas, sometimes called the Five Dhyani Buddhas. They are Akshobya, the blue Buddha of the East, Ratnasambhava, the yellow Buddha of the South, Amitabha, the red Buddha of the West, Amoghasiddhi, the green Buddha of the North and Vairocana, the white Buddha at the centre of the Mandala. Each Buddha represents enlightenment in its totality and perfection and each represents or emphasises an aspect of enlightenment, a mundane quality taken to perfection. I think the quality of Kshanti when perfected, could be best illustrated by the figure of Akshobya. Akshobya, the blue Buddha, sits on a lotus throne which is supported by four elephants and his mudra or hand gesture is called the bhumisparsa mudra or earth-touching mudra. Akshobya is also associated with transforming the poison of hatred or anger into the energy that breaks through obstacles. The wisdom of Akshobya is known as the mirror-like wisdom. The word ‘aksobhya’ means unshakeable and the Buddha Akshobya is The Unshakeable or The Imperturbable.

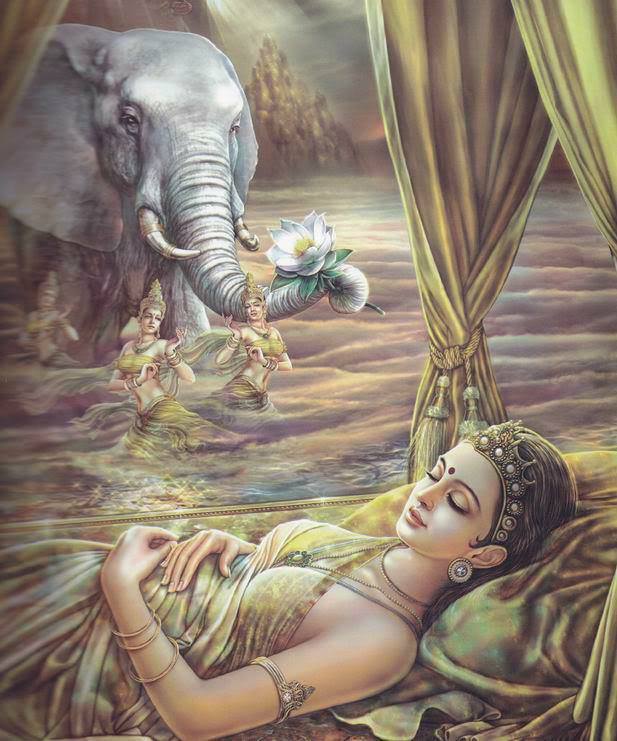

In “Meeting the Buddhas”, Vessantara tells us how Akshobya got his name: “Ages ago, in a land called Abhirati (intense delight) a Buddha called Vishalaksha was faced with a monk who wanted to vow to gain Enlightenment for the sake of all living beings. The Buddha warned him that he would be undertaking a daunting task, as to attain his goal he would have to forswear all feelings of anger. In response, the monk took a series of great vows: never to give way to anger or bear malice, never to engage in the slightest immoral action, and many others. Over aeons he was unshakeable (aksobhya in Sanskrit) in holding to his vow, and as a result he became a Buddha of that name, and created a Pure Land or Buddha Field”. (7)

So anger is highlighted here as the emotion we have to really transform if we are to be of benefit to others spiritually. It is said that it is better for an aspiring Bodhisattva to experience craving that hatred, because hatred denies the interconnectedness of humanity and is therefore totally opposed to all that the spiritual life is about. So the energy of hatred or anger has to be channelled in a positive direction. We need energy to practise the Dharma, to break through our hindrances, limitations and blindness. Often that energy is bound up with negative emotions, protecting our ego-identity, defending our comfort zones, blaming our suffering on others and so on. It is our task to use the tools of meditation, mindfulness, spiritual friendship and study to gradually channel our energy more positively, to help us break through our fears and self-imposed limitations. To do this we have to learn to be patient, to introduce a gap between any experience of being hurt or misunderstood, and our response to that experience. We need to learn to forgive others for their imperfections and insensitivity. We need to learn how to disagree without being intolerant. And we need to be receptive to the vast perspective of the Dharma and allow it to change us. When we practise in this way, we will begin to experience something of the tranquillity and stability that is given such sublime expression in the figure of the Buddha Akshobya, the Imperturbable. We will also be training ourselves in the practice of Kshanti, one of the virtues most characteristic of the bodhisattva.

Notes: 1. Kim, Rudyard Kipling 2. The Ten Pillars of Buddhism, Sangharakshita 3. Seminar on The Jewel Ornament of Liberation, Chapter 14 4. The Drama of Cosmic Enlightenment, Sangharakshita 5. Majjhima-Nikaya, quoted in The Survey of Buddhism 6. The Dhammapada, translated by J. Mascaro 7. Meeting the Buddhas, Vessantara Kshanti .

Source: http://ratnaghosa.fwbo.net

Add a comment