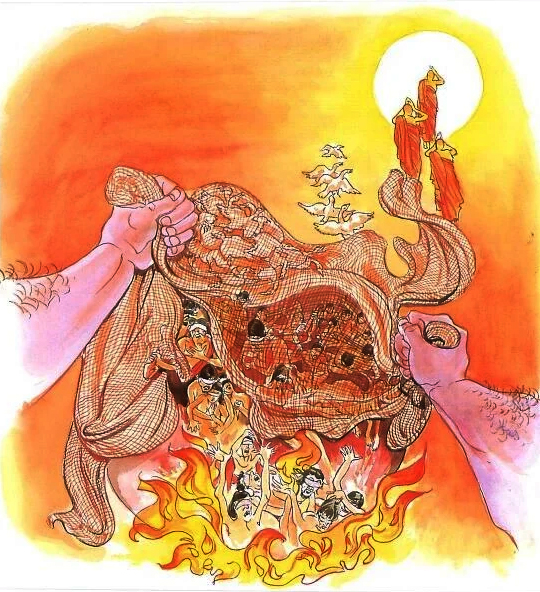

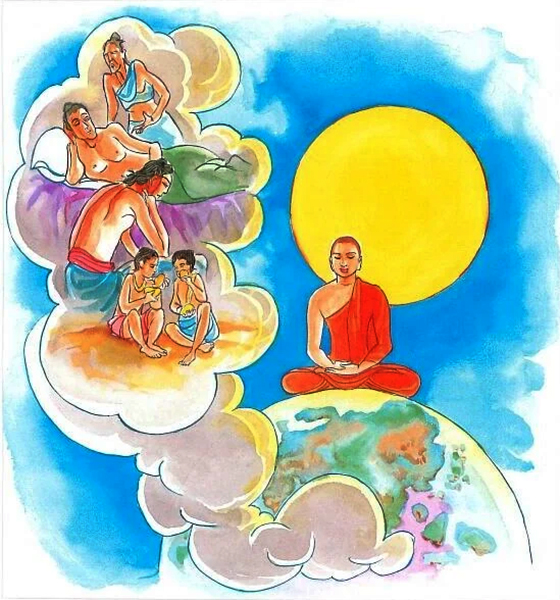

Verse 172: He, who has been formerly unmindful, but is mindful later on, lights up the world with the light of Magga Insight as does the moon freed from clouds.

The Story of Thera Sammajjana

While residing at the Jetavana monastery, the Buddha uttered Verse (172) of this book, with reference to Thera Sammajjana.

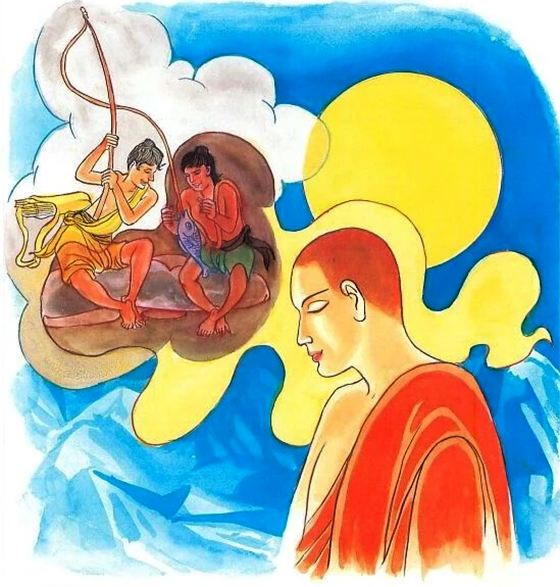

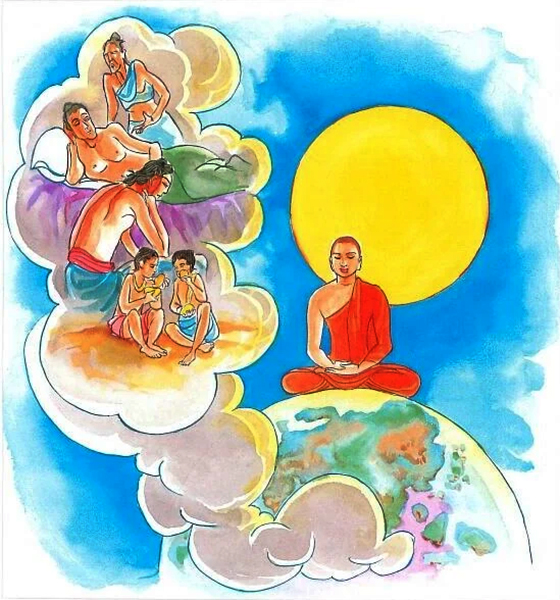

Thera Sammajjana spent most of his time sweeping the precincts of the monastery. At that time, Thera Revata was also staying at the monastery; unlike Sammajjana, Thera Revata spent most of his time in meditation or deep mental absorption. Seeing Thera Revata’s behaviour, Thera Sammajjana thought the other thera was just idling away his time. Thus, one day Sammajjana went to Thera Revata and said to him, “You are being very lazy, living on the food offered out of faith and generosity; don’t you think you should sometimes sweep the floors or the compound or some other place?” To him, Thera Revata replied, “Friend, a bhikkhu should not spend all his times sweeping. He should sweep early in the morning, then go out on the alms-round. After the meal, contemplating his body he should try to perceive the true nature of the aggregates, or else, recite the texts until nightfall. Then he can do the sweeping again if he so wishes.” Thera Sammajjana strictly followed the advice given by Thera Revata and soon attained arahatship.

Other bhikkhus noticed some rubbish piling up in the compound and they asked Sammajjana why he was not sweeping as much as he used to, and he replied, “When I was not mindful, I was all the time sweeping; but now I am no longer unmindful.” When the bhikkhus heard his reply they were sceptical; so they went to the Buddha and said, “Venerable Sir! Thera Sammajjana falsely claims himself to be an arahat; he is telling lies.” To them the Buddha said, “Sammajjana has indeed attained arahatship; he is telling the truth.” Continue reading →