Even in Hell there was Compassion

Today I would like to speak a little bit about Heaven, or Paradise, and Hell. I have been in Paradise, and I have been in Hell also, so I have some experience to share with you. I think if you remember well, you know that you have also been in Paradise, and you have also been in Hell. Hell is hot, and it is difficult.

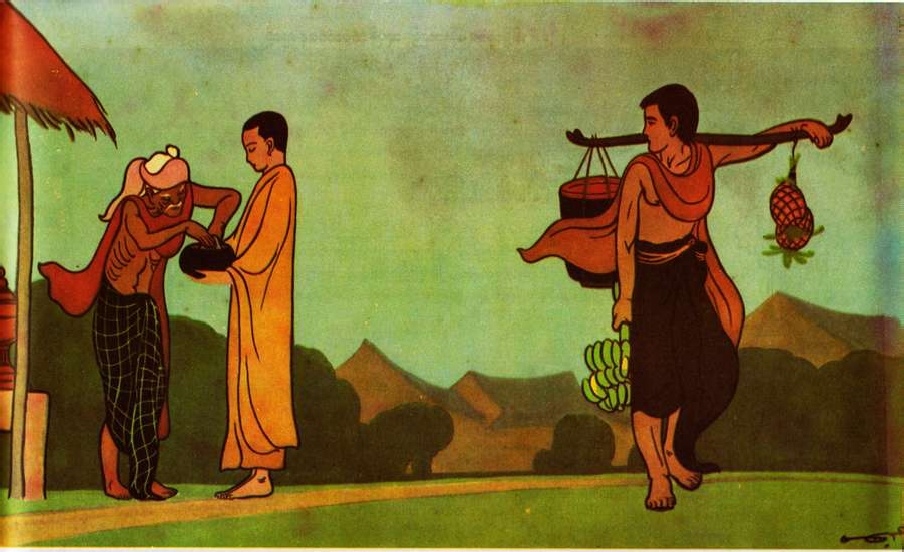

The Buddha, in one of his former lives, was in Hell. Before he became a Buddha he had suffered a lot in many lives. He made a lot of mistakes, like all of us. He made himself suffer, and he made people around him suffer. Sometimes he made very big mistakes, and that is why in one of his previous lives he was in Hell. There is a collection of stories about the lives of the Buddha, and there are many hundreds of stories like that. These stories are collected under the title Jataka Tales. Among these hundreds of stories, I remember one very vividly. I was seven years old, very young, and I read that story about the Buddha, and I was very shocked. But I did not fully understand that story.

The Buddha was in Hell because he had done something wrong, extremely wrong, that caused a lot of suffering to himself and to others. That is why he found himself in Hell. In that life of his, he hit the bottom of suffering, because that Hell was the worst of all Hells. With him there was another man, and together they had to work very hard, under the direction of a soldier who was in charge of Hell. It was dark, it was cold, and at the same time it was very hot. The guard did not seem to have a heart. It did not seem that he knew anything about suffering. He did not know anything about the feelings of other people, so he just beat up the two men in Hell. He was in charge of the two men, and his task was to make them suffer as much as possible.

I think that guard also suffered a lot. It looked like he didn’t have any compassion within him. It looked like he didn’t have any love in his heart. It looked like he did not have a heart. He behaved like a robber. When looking at him, when listening to him, it did not seem that one could contact a human being, because he was so brutal. He was not sensitive to people’s suffering and pain. That is why he was beating the two men in Hell, and making them suffer a lot. And the Buddha was one of these two men in one of his previous lives.

The guard had an instrument with three iron points, and every time he wanted the two men to go ahead, he used this to push them on the back, and of course blood came out of their backs. He did not allow them to relax; he was always pushing and pushing and pushing. He himself also looked like he was being pushed by something behind him. Have you ever felt that kind of pushing behind your back? Even if there was no one behind you, you have felt that you were being pushed and pushed to do things you don’t like to do, and to say the things you don’t like to say, and in doing that you created a lot of suffering for yourself and the people around you. Maybe there is something behind us that is pushing and pushing. Sometimes we say horrible things, and do horrible things, that we did not want to say or do, yet we were pushed by something from behind. So we said it, and we did it, even if we didn’t want to do it. That was what happened to the guard in Hell: he tried to push, because he was being pushed. He caused a lot of damage to the two men. The two men were very cold, very hungry, and he was always pushing and beating them and causing them a lot of problems.

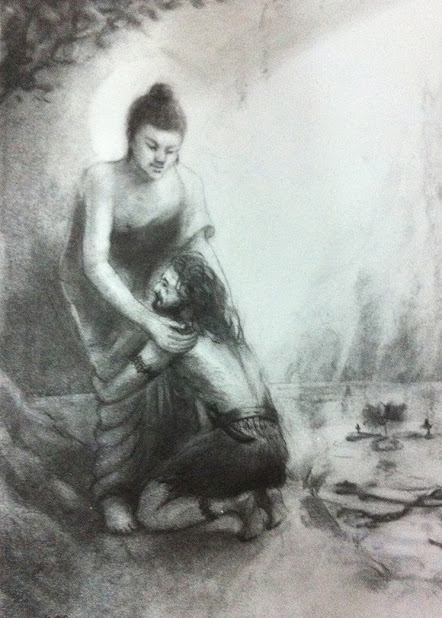

One afternoon, the man who was the Buddha in a former life saw the guard treating his companion so brutally that something in him rose up. He wanted to protest. He knew that if he intervened, if he said anything, if he tried to prevent the guard beating the other person, that he would be beaten himself. But that something was pushing up in him, so that he wanted to intervene, and he wanted to say: “Don’t beat him so much. Why don’t you allow him to relax? Why do you have to stab him and to beat him and to push him so much?” Deep within the Buddha was a pressure coming up, and he wanted to intervene, even knowing perfectly well that if he did, he would be beaten by the guard. That impulse was very strong in him, and he could not stand it anymore. He turned around, and he faced the guard without any heart, and said, “Why don’t you leave him alone for a moment? Why do you keep beating him and pushing him like that? Don’t you have a heart?”

That was what he said, this man who was to be the Buddha. When the guard saw him protesting like that, and heard him, he was very angry, and he used his fork, and he planted it right in the chest of the Buddha. As a result, the Buddha died right away, and he was reborn the very same minute into the body of a human being. He escaped Hell, and became a human being living on earth, just because compassion was born in him, strong enough for him to have the courage to intervene to help his fellow man in Hell.

When I read this story, I was astonished, and I came to the conclusion that even in Hell there was compassion. That was a very relieving truth: even in Hell there is compassion. Can you imagine? And wherever compassion is, it’s not too bad. Do you know something? The other fellow saw the Buddha die. He was angry, and for the first time he was touched by compassion: the other person must have had some love, some compassion to have the courage to intervene for his sake. That gave rise to some compassion in him also. That is why he looked at the guard, and he said, “My friend was right, you don’t have a heart. You can only create suffering for yourself and for other people. I don’t think that you are a happy person. You have killed him.” And after he said that, the guard was also very angry at him, and he used his fork, and planted the fork in the stomach of the second man, who also died right away, and was reborn as a human being on earth. Both of them escaped Hell, and had a chance to begin anew on earth, as full human beings.

What happened to the guard, the one who had no heart? He felt very lonely, because in that Hell there were only three people and now the other two were dead. He began to see that these two were not very kind, or very nice, but to have people living with us is a wonderful thing. Now the two other people were dead, and he was alone, utterly alone there. He could not bear that kind of loneliness, and Hell became very difficult for him. Out of that suffering he learned something: he learned that you cannot live alone. Man is not our enemy. You cannot hate man, you cannot kill man, you cannot reduce man to nothingness, because if you kill man, with whom will you live? He made a vow that if he had to take care of other people in Hell, he would learn how to deal with them in a nicer way, and a transformation took place in his heart. In fact, he did have a heart. To believe that he did not have a heart is wrong—everyone has a heart. We need something or someone to touch that heart, to transform it into a human heart. So this time the feeling of loneliness, the desire to be with other humans, was born in him. That is why he decided that if he had to guard other people in Hell, he would know how to deal with them with more compassion. At that time, the door of Hell opened, and a bodhisattva appeared, with all the radiance of a bodhisattva. The bodhisattva said, ” Goodness has been born in you, so you don’t have to endure Hell very long. You will die quickly and be reborn as a human very soon.”

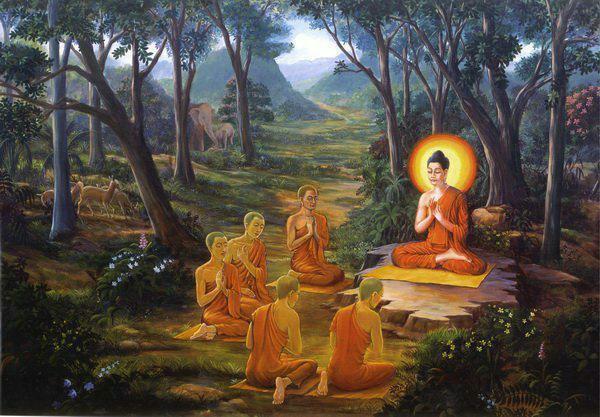

That is the story I read when I was seven. I have to confess that at the time I read it I did not understand it fully. Nevertheless, the story had a strong impact on me. I think that was my favorite Jataka tale. I found that in Hell, there can be compassion. It is possible for us to give birth to compassion even in the most difficult situations. In our daily lives, from time to time, we create Hell for ourselves and for our beloved ones. The Buddha had done that several times before he became a Buddha. He created suffering for himself and for other people, including his mother and his father. That is why, in one of his former lives, he had to be in Hell. Hell is a place where we can learn a lesson in order to grow, and the Buddha learned well in Hell. Do you know what happened after he was reborn as a human? He continued to practice compassion, and from that day on he continued to make progress in the direction of understanding and love, and he has never gone back to Hell again, except when he wanted to go there and help the people who suffer.

I have been in Hell, many kinds of Hell, and I have also noticed that even in Hell compassion is possible. With the practice of Buddhist meditation, you may very well prevent Hell manifesting. And if Hell has manifested, you have ways to transform Hell into something that is much more pleasant. When you get angry, Hell is born. Anger makes you suffer a lot, and not only do you suffer, but the people you love also suffer at the same time. When we don’t know how to practice, from time to time we create Hell in our own families. When we went to school, our teachers never helped us to deal with these difficulties. He or she did not teach us how to transform Hell into something better, like Paradise. But when you come to a practice center like Plum Village, the brothers and sisters who live here will be able to tell you how to prevent Hell manifesting. If it happens that Hell is there, what can you do for Hell to be transformed into an atmosphere of calm, of coolness, of joy?

Today I would like the young people to learn more about this practice of transforming Hell into something that is more pleasant. You know that the practices of mindful breathing, of mindful walking, of smiling, are very important. You think that you can walk—of course you can walk. You think that you can breathe—in fact, you breathe every day, all day and all night. You think that you can smile. Yes, but the smile here is a little bit different, the breath here is a little bit different, the walking here is a little bit different. We call it mindful breathing, mindful walking, mindful smiling, and if you master these methods of practice, you have instruments to transform Hell into Heaven.

Hell can be created by Father, or Mother, or sister, or brother, or yourself. You have created Hell many times in your family, and every time Hell is there, not only do the other people suffer, but you also suffer. So how to make compassion arise in one of you? I think that is the key of the practice. If among you three or four people, there is one person who has compassion inside, one person who is capable of smiling mindfully, of breathing mindfully, of walking mindfully, she or he can be the savior of the whole family. He or she will play the role of the Buddha in Hell, because compassion is born in him first, and that compassion will be seen and touched by someone else, and someone else. It may be that Hell can be transformed in just one minute or less. It is wonderful!

Transforming Negative Habit Energies

Dharma Talk given on August 6, 1998 in Plum Village, France.

by Thich Nhat Hanh