The Story of Three Groups of Persons

Verse 127: Not in the sky, nor in the middle of the ocean, nor in the cave of a mountain, nor anywhere else, is there a place, where one may escape from the consequences of an evil deed.

The Story of Three Groups of Persons

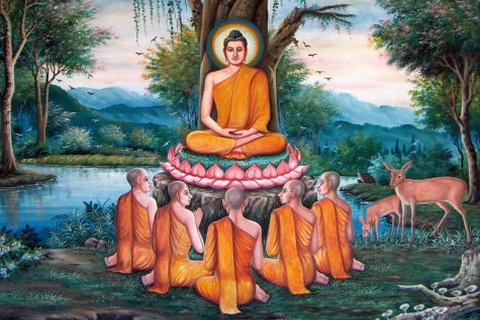

While residing at the Jetavana monastery, the Buddha uttered Verse (127) of this book, with reference to questions raised by three groups of bhikkhus concerning three extraordinary incidents.

The first group: A group of bhikkhus were on their way to pay homage to the Buddha and they stopped at a village on the way. Some people were cooking alms-food for those bhikkhus when one of the houses caught fire and a ring of fire flew up into the air. At that moment, a crow came flying, got caught in the ring of fire and dropped dead in the central part of the village. The bhikkhus seeing the dead crow observed that only the Buddha would be able to explain for what evil deed this crow had to die in this manner. After taking alms-food they continued on their journey to pay homage to the Buddha, and also to ask about the unfortunate crow.

The second group: Another group of bhikkhus wore travelling in a boat; they too wore on their way to pay homage to the Buddha. When they were in the middle of the ocean the boat could not be moved. So, lots were drawn to find out who the unlucky one was; three times the lot fell on the wife of the skipper. Then the skipper said sorrowfully, “Many people should not die on account of this unlucky woman; tie a pot of sand to her neck and threw her into the water so that I would not see her.” The woman was thrown into the sea as instructed by the skipper and the ship could move on. On arrival at their destination. the bhikkhus disembarked and continued on their way to the Buddha. They also intended to ask the Buddha due to what evil kamma the unfortunate woman was thrown overboard. Continue reading